The Chateau Marmont, which was modeled loosely after the Chateau d’Amboise, a royal retreat in France’s Loire Valley, is a timeless Los Angeles landmark that evokes old Hollywood glamour. Yet fine artist Paul Julien Freed has managed to find modern inspiration at the famed Marmont, after years spending time there as a home away from home. Drawing on inspiration from his personal journey with cancer as well as his professional experience as a film editor and commercial director, Freed allows history and technique to inform his career as a painter. As he explains, “Visually, I work on revealing deepening layers of the physical world in order to expose how frail and arbitrary life can seem.”

Freed’s artistic journey has been singular and unconventional, which is fitting for an artist exhibiting his work at a storied Hollywood Chateau. Freed tells JustLuxe about his path so far and what’s next for him.

Tell me a bit about your upcoming art show at Chateau Marmont.

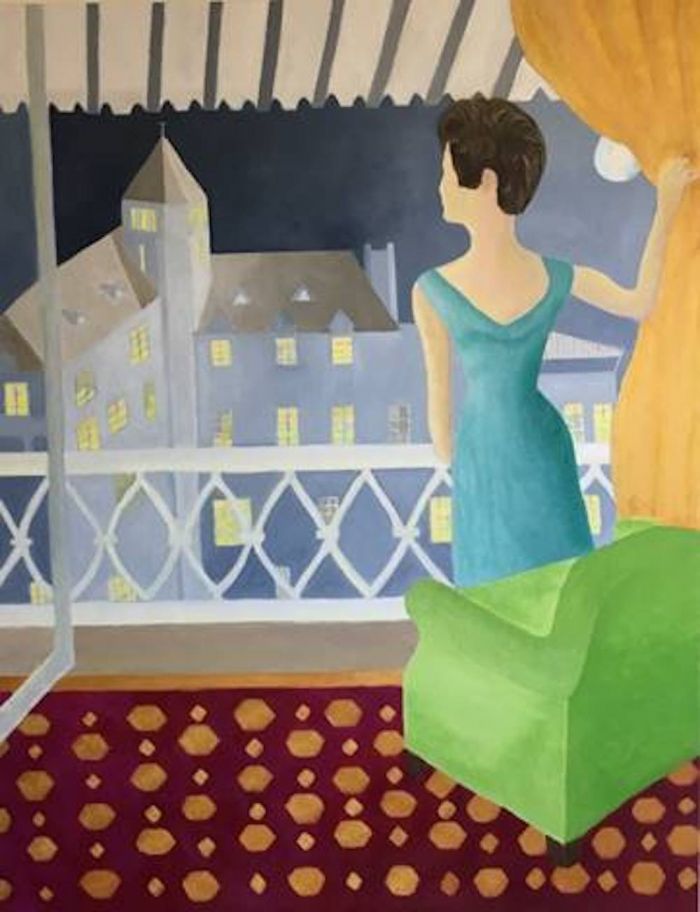

The show will be held in a suite at the Chateau Marmont. The centerpiece will be my 60x48 oil painting, Chateau. It will also include 15-20 paintings curated from my work of the last few years. What appeals to me, historically, about holding the show in what is essentially an apartment is that the Impressionist salon of 1876 was curated and held in an apartment in Paris. I have always been drawn to Impressionism and the painters associated with that movement.

That’s a unique place to have an exhibit. How did that come about?

My wife, Nan, and I have alternately stayed and lived at the Chateau Marmont since the 1980s. For a certain group of people, mostly working in film in Los Angeles, the hotel was a magnet and safe haven. My wife is a producer for feature films and television and I was an editor. Over the years, we have built personal relationships with many of the people who work there. It’s not unlike Rick’s Cafe in Casablanca. When Bogart sells the Cafe to Sydney Greenstreet he stipulates that the people who work there must be kept on. Greenstreet replies: “Of course. Rick’s wouldn’t be Rick’s without them.” I may have slightly paraphrased the quote, but replace “Rick’s” with “Chateau Marmont” and you catch the drift.

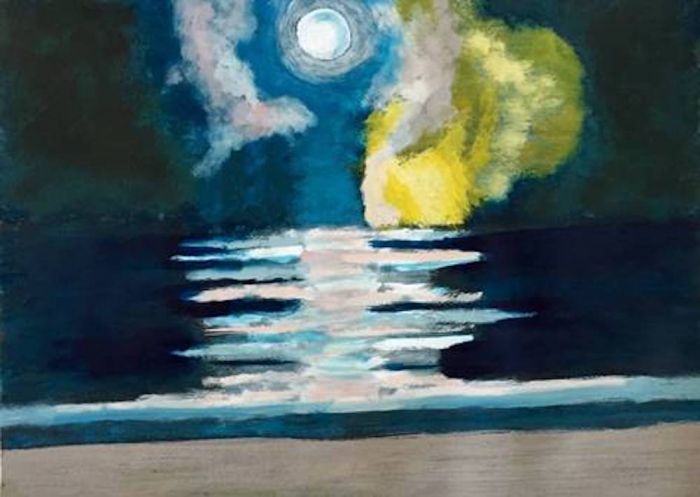

When we returned to Los Angeles in 2011, after living in Austin, Texas for nearly six years while my wife produced the series Friday Night Lights, we first lived, where else? but at the Chateau Marmont. One evening we walked our two dogs up into the hills behind the hotel. When I looked back, I saw the dark yet distinct outline of the Marmont with a full moon hanging overhead. I took some quick photos on my iPhone and filed them away until the idea for Chateaucrystalized.

How long have you been an artist?

As I mentioned above, I’ve been working as an artist/painter for approximately five years. I began after my fourth cancer surgery in 2013. At the time, I was looking for a way to regain the focus I had prior to this last surgery. As in my previous work as an editor and in advertising, I have a strong sense of design and color. So I turned to painting and literally just began, as I do with most things in my life. I’ve always operated under the premise that if I can visualize something I can do it. So I wasn’t surprised that my efforts evolved. But I was a bit surprised at how quickly they evolved. I was showing in group shows inside of a year from when I began. And have shown four times since.

Which artist has most influenced you and how?

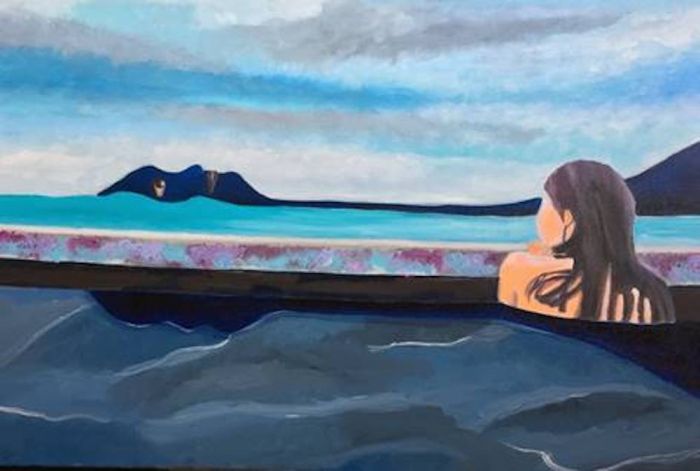

Gustave Caillebotte is the artist who was the inspiration for Chateau. He was considered part of the Impressionist movement in France but curiously not considered on the same level as the more well-known impressionists, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Manet, etc., in part because he also acted as their patron. His father was a wealthy merchant, part of the nouveau riche coming to the fore in France at that time. Caillebotte collected his friends’ paintings, supported them financially, and organized the 1876 salon in Paris. His most famous works are, of course, Paris Street, Rainy Day, The Floor Scrapers, and The Pont De L’Europe. What attracted me to him originally was his understanding of photographic technique, cropping, perspective, etc., at a time when photography was still a relatively young art and technology. But most especially his use of deep focus, fifty plus years before its use in German Expressionist films or, most notably, movies like Citizen Kane. His portraits of people contemplating something inside the painting, admiring the same thing as the artist and the viewer inspired Chateauand the paintings I’m planning for the near future.

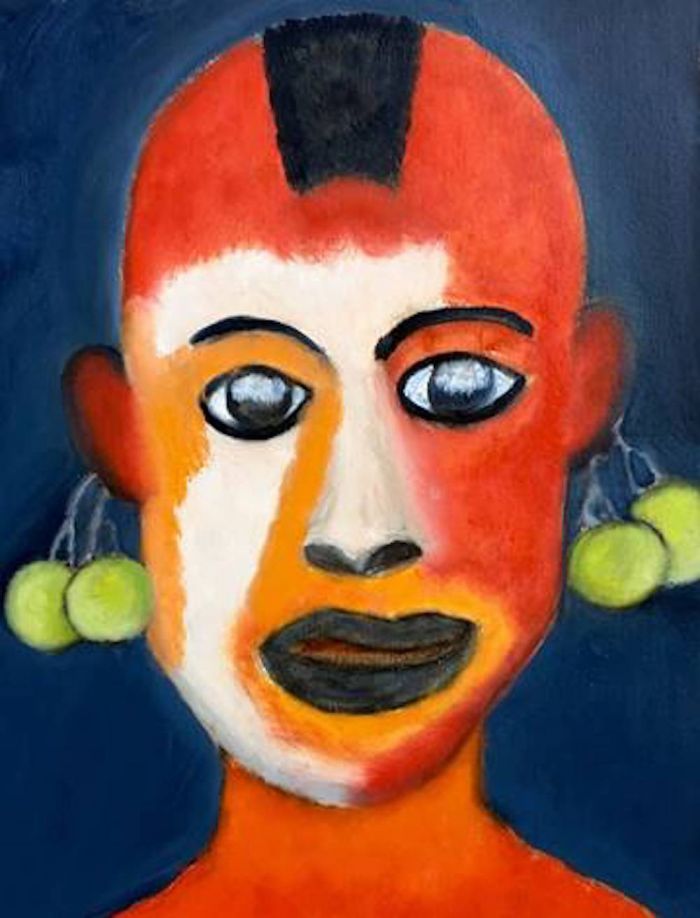

How would you describe your style?

Photography and design strongly influence my work. I would say I’m a figurative painter interested in creating narratives that reach beyond the confines of the frame itself as well as being expressed through the colors I use in my work. Chateauis a prime example. The woman in this painting is standing inside a room full of color in front of an open balcony window. She is communing with the Chateau Marmont—whose colors are desaturated by the moonlight—through this window which frames the world outside in revealing and unexpected ways.

You worked in the film industry as an editor for many years. How do you feel that influenced your artwork, if it has?

My years as a film editor began when I owned a trailer company, creating advertising campaigns for movies. Other than design and copy for print ads, trailers and TV spots are an editing function. I was asked at one point if I’d be interested in editing someone’s feature film and wound up spending the next years editing feature films, TV movies and series.

I’ve often described editing as the last stage in the writing process. The first stages, of course, are the script itself and casting. The arguments I’ve seen directors and producers have late at night in the editing room usually revolve around problems that can only be resolved to a point through editing. If the script wasn’t written and/or cast correctly, there’s only a certain amount a good editor can achieve.

It’s the same with my painting. If I haven’t planned and/or sketched the concept properly, I will never be able to fully or properly realize my vision. When I do begin with a sketch, I consider it to be the foundation for what is to follow. If done correctly, it allows me the freedom to work in directions I may not have anticipated. For instance, I spent nearly two weeks on the sketch for Chateau.

On your site you say that “memory can best be preserved with acceptance rather than suffering.” Could you elaborate? And: You were diagnosed with a rare form of cancer and had to confront your mortality. How do you feel that’s influenced your perspective on life and on your art?

These two questions relate to my illness. So I will answer them as one. In 2005, I was diagnosed with a rare cancer. So rare that the doctors have identified less than forty cases in the past thirty years, worldwide. So rare that there’s no name for it. The doctors refer to it by the malignant cells that combine to create these particular types of tumors.

These past thirteen years have changed my life, beyond the obvious that I began painting because I was recovering from multiple surgeries. Many of the qualities I might not have been completely in touch with before, I now embody: patience, compassion, empathy, emotional endurance and stability. And those I did have before—strength, resilience, focus, hope—have a new emphasis and meaning. All these qualities—old and new friends—manifest themselves in my work.

When I say that “memory can best be preserved with acceptance rather than suffering” I mean that I will never let myself be defined by cancer. I’m an artist/painter who happens to have an illness, not a cancer patient who is also an artist. There are very few people who know and understand what I physically and emotionally deal with every day. That is by design. A man or woman’s power is in the half-light, in the unseen and unheard. My wife and I first discussed this in 2005. One of my priorities was to model for everyone we knew how to walk through life with serious illness. Never to complain or be without hope. And if and when my life came to an end, to show that death was not a separate entity but rather an integral part of life itself. I’ve visualized at least thirty more productive years for myself and as I mentioned earlier, if I can visualize something I can do it. But in reality, none of us know how long we have in this life. It’s just a little more immediate for me.

There’s an expression I’m sure you’ve heard before: “pay it forward.” When I was first diagnosed in 2005, friends and acquaintances who’d already been through similar experiences stepped up to help me, make me aware of what to expect, and encourage me to move forward positively. All any of them asked in return was that I do the same for those who came after me. And that’s exactly what I’ve endeavored to do. I’ve worked with kids at children’s hospitals in Los Angeles and Dell Children’s Hospital in Austin, Texas. And I’ve worked with adults who’ve been diagnosed and reached out to me through mutual friends. It’s the least I can do and has certainly informed my work as well.

What would you like your audience to take away from your work?

This is a tricky question. I'm loathed to even title any of my paintings. I do it strictly for marketing and reference purposes. The viewer should, ideally, see one of my paintings without in any way being led to or pointed toward a conclusion. He or she should see it for the first time and have a visceral reaction free of any analysis or background on the artist.

I know this is an idealistic and, therefore, unrealistic viewpoint. But to refer to a Warhol quote for a moment: “The idea is not to live forever, it is to create something that will.” That is what I’m working toward. To create something that will resonate long after I’m gone and in some small way contribute to moving the human condition forward in a positive way.

Where can people see your artwork?

People can currently see my artwork on my website: www.pjfreed.com

Paul Julien Freed has exhibited his work nationally and has been included in five shows in Los Angeles. In addition, his work has appeared on Showtime’s I’m Dying Up Here and Hulu’s Chance. Freed’s work is remarkable and personal. As he explains, “All of my paintings are meant to memorialize my physical existence against what is closely confronting me: the ephemeral.”