The fact is, unexpected adventures stick with you. And, if you are a writer, or even if you are not, you either write about them or tell them to others. The goal is to remember what happened and how you were affected.

I was at The Hideout Lodge & Guest Ranch in Shell, Wyoming some years ago, writing for two publications, about this unique place – a Guest Ranch at the base of the Big Horn Mountains in northern Wyoming. The Hideout was one of those places that is difficult to get to – about two hours east of Cody, Wyoming; but so worth it once there: great horse adventures, exceptional food, clean air, peace and quiet, a true sanctuary of the West.

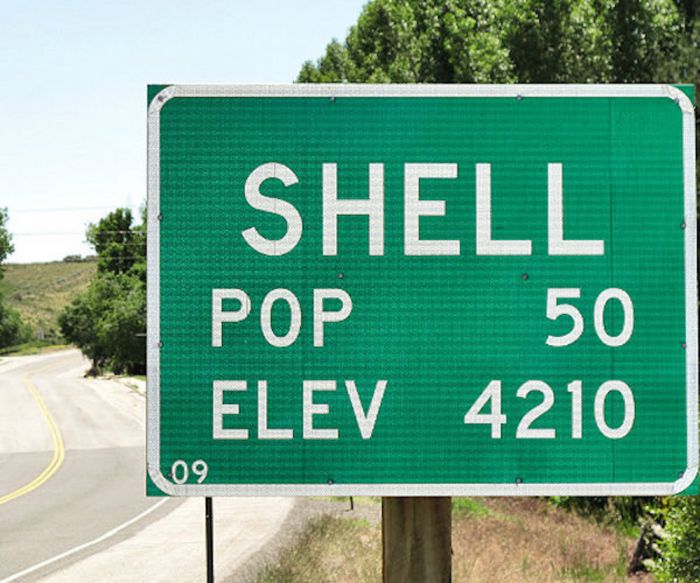

The Hideout Guest Ranch experience offered then, and now, a strong sense of place, daily adventure, and promoted a deep love and respect for the nature that surrounds it. And it is in Shell, Wyoming, population 50, when I was there. I had an experience while I was in Shell, not at the Hideout. But it was because of the Hideout that I had this adventure, so I am, even so many years later, deeply grateful.

At The Hideout, they had many daily excursions for the guests. There were were day long or hours long trail rides, but also,there were Dinosaur hunts. I chose the latter, only because I had never been on one, and had never seen an actual Dinosaur track in ancient prehistoric mud flats. Another Hideout guest, John, also came on this Dinosaur hunt. All I knew about him was that he was not a horseman, and his cell-phone didn’t work very well. But he came with us, and marveled, like the rest of us, at the Dinosaur tracks in the ancient mud.

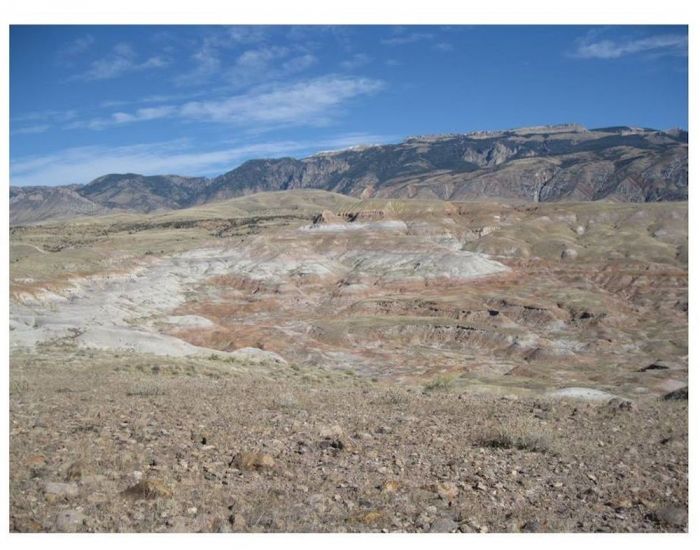

Our guides were Clifton and Ruth, a husband and wife team who were impassioned about fossils, the Jurassic period, what the mountains told us, what the stones disclosed. In the first few hours, we were consumed by walking along tidal areas where we actually saw Dinosaur footprints. Clifton put a poker chip near one of them, so we could see what the foot indentations looked like. Clifton explained that the Smithsonian Musuem and Harvard University had multiple digs around there, as he explained that it had only been about a million years ago that Wyoming – indeed most all of the West -- had been slightly above but mostly below water. Where we were standing was at one time deep tidal pools.

When we finished with the tidal basin, Clifton and Ruth and drove us across the highway down an old road, to a working ranch. On private land, we drove up into the hills, and then down into a crevice. Clifton knew of an exceptional archaeological dig where the diligent workers had recently uncovered one intact Stegosaurus skeleton. He knew they were working on uncovering more. The van stopped and we climbed up a steep hill – then, down into a valley.

There was the dig --one where only a few dedicated, dusty people worked with brushes and small, delicate chisels. What they found thus far was a skull of what they thought was another Stegosaurus, then down about 20 feet away were the remains of his or her vertebra. The lead paleontologist, Bob Simon, told us about the ancient creature, but all I wanted to do was touch the skull, and did. John followed, and touched it also.

As we touched, we saw the outlines of this archeological reality, but standing away from it, it also looked very much like a common rock we might have cleared away in our backyards. But through the dust-creased lines, it looked like it was smiling. An old, indented 250 million year old smile: ancient past and dusty present, equally parsed.

When I asked Bob if he thought there were any more ancient creatures embedded in the hills, I remember him saying something like, “ Yes! In fact, every night I hear the hills laughing! Of course, they are there. We just haven’t found them yet.”

When walking back to the van, I said to John, “How small we seem, and what is it that we are worried about today? Maybe that’s was what that creature was smiling about. In the grand scheme, it’s all small stuff.”

I looked at John, who by this time had a ruddy complexion. His glistening silver hair was damp with sweat. I told him my knees hurt from all this walking up and down. And then he said, out of the blue, “I have a cancerous melanoma and have been given four of five months to live.” I looked at him, he smiled and tilted his head. He then said he had refused more radiation, as he wanted to live out his days without being in more radiation-caused pain. I said something about having thoughts too deep for tears, and offered my condolences. I began thinking that the confluence of past and present, the touch of something so ancient, and the dusty lines of the 250-million-year-old smile must have affected him, lightening, possibly, yet paradoxically, the profound burden of a darkening life.

As we drove back, I looked at the hills with a new reverence, understanding that John’s disclosure of acceptance of the inevitable came a perfect time. The past smiled on the present, and the present reciprocated: the Stegosaurus smiled, and John did, too.